In April 1955, a 57-year-old Zhou Enlai stood before representatives of 29 Asian and African nations in Bandung, Indonesia. Only five-and-a-half years after the founding of the People's Republic, China's premier was making his first major appearance on the world stage. The stakes could hardly have been higher. Many delegates arrived skeptical of Chinese intentions; memories of imperial China's tributary system lingered, and Zhou's task was to convince delegates that the new China stood with them as fellow victims of Western imperialism, not as a potential new hegemon.

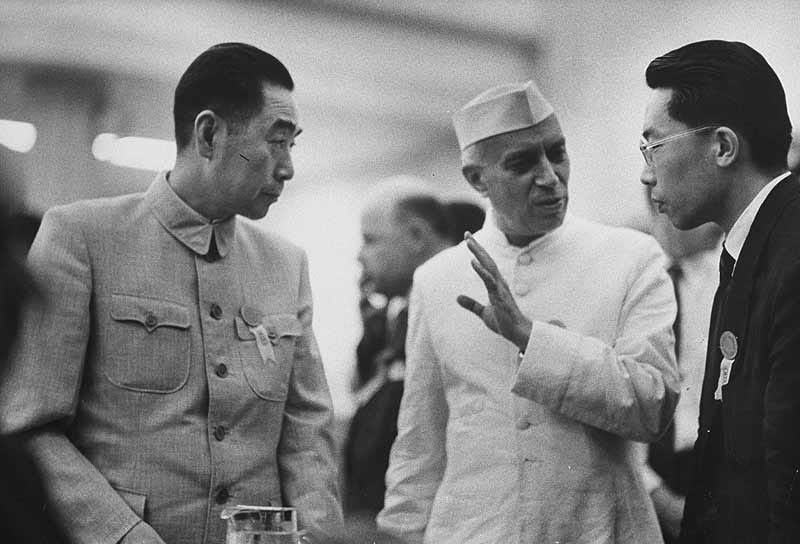

Zhou's performance was masterful. The polyglot premier worked the conference halls and private meetings, projecting both sophistication and solidarity. When India's Nehru praised Zhou's diplomatic prowess at Bandung, he was acknowledging something remarkable: China had presented itself not as an empire reborn, but as a partner on the path to postcolonial dignity.

Seven decades later, Chinese diplomats still invoke the "Spirit of Bandung" when addressing audiences in the Global South, whether at BRICS summits or at FOCAC, the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation. Yet China now finds itself in a position Zhou could scarcely have imagined: The same China that once championed postcolonial solidarity finds itself accused of engaging in the very practices Bandung was meant to resist. Its Belt and Road Initiative is called "debt-trap diplomacy" by critics. Its extensive mining and infrastructure projects across Africa and Latin America draw charges of "neo-colonialism." Its domestic policies in Xinjiang and Tibet are labeled "settler colonialism" and worse by academic critics.

The Blind Spot of Anti-Colonial Identity

Chinese intellectuals now face a profound challenge: how to reconcile their civilization's deeply embedded narrative of colonial victimhood with their country's current role as a global power. At stake is nothing less than how China understands itself and its place in a world that looks increasingly multipolar but whose power relations still bear the deep imprint of colonial history.

While terms like 'neo-colonialism' and 'settler colonialism' are often applied too readily to Chinese actions, the deeper truth may be that China's very identity as an anti-colonial nation makes it difficult to recognize when its practices echo colonial patterns. China's own anti-colonial identity is not merely rhetorical but constitutive of its modern state and national consciousness, which paradoxically may blind it to similarities between some of its current actions and historical colonial practices it once resisted.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Sinica to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.