“This Week in China’s History” is free for everyone this week. If you like this column and would like to continue reading it and the many other offerings from Sinica, please support our work by becoming a paid subscriber!

The notion of China’s unity has been a subject of myth and legend for millennia. Notwithstanding that it is a work of fiction, or that the quotation at its start was not original to the novel, but written by later editors, the Romance of the Three Kingdoms opening carries the power of destiny for Chinese patriots: ”The empire, long divided, must unite; long united, must divide. Thus it has ever been.” As I have written before — in the early days of this column — the idea of “China” (like any nation-state) is complicated. Its geographic, linguistic, cultural, and political boundaries varying over time, much more than an empire cyclically dividing and then reuniting. But, for nationalists, history is a tool, not an end in itself.

With that in mind, Chiang Kai-shek was certainly familiar with those opening lines, written in the Ming-Qing transition to describe the era following the Han dynasty. In the spring of 1927, Chiang may have had them on his mind as he implemented the Northern Expedition, the latest attempt to unite “the empire, long divided.” China had disintegrated following the failure of Yuan Shikai’s government, leaving a patchwork of fiefdoms and mini- and, in some cases, micro-states. While militarists fought for control of Beijing, Sun’s KMT reorganized in Canton. Everyone’s objective was to “reunify” the country — that is, to establish a Chinese-led state with the borders of the Qing dynasty — but who would be able to manage it?

When Sun died in the spring of 1925, he had developed the plans for a campaign that would defeat, or co-opt, the warlord armies and establish KMT control over a unified, centralized Chinese republic. But after his death, the party he had founded was just as divided as the country he aspired to lead. The party’s early history was dominated by a rift between its left wing — supported by the Soviet Union — and its right wing — tinged with fascism. Members of the Communist Party were automatically members of the KMT under terms of the United Front, but the contradictions were plain to see. (The pushme-pullyu nature of the party was symbolized by the Whampoa Military Academy, where men who would later face each other on battlefields and across negotiating tables lived and studied together.) Sun managed to keep the competing sides aligned despite the tensions, but once he was gone, a split seemed inevitable.

It was in this context that Chiang Kai-shek, the leader of the KMT’s National Revolutionary Army (NRA), began consolidating power. He used the pretext of the 1926 “Canton Coup” to purge many Communist elements from the KMT while simultaneously appealing to the Soviet Union for support. This skillful maneuver made Chiang preeminent within the party, and also cleared the way for the Northern Expedition, which the purged Communists had opposed. The KMT forces launched out of their Guangzhou base in the summer of 1926, moving quickly to capture Changsha and other cities. Although the Northern Expedition — as its name suggests — was an attempt to unify China from North to South, it was not a systematic campaign. Regional alliances and the ebb and flow of military and political fortunes made for a rapidly shifting battlefield.

Nonetheless, after nine months of fighting, most of China south of the Yangtze had come under KMT control.

The fight for Shanghai was critical. China’s largest city was also its most industrial, and the birthplace of the Communist Party. Labor unions played a stronger political role there than in any other city in the country — there were nearly 500 unions in the city, with more than 800,000 members. Led by Zhou Enlai and Chen Duxiu, it was union workers, not soldiers, who seized control of Shanghai from the warlord forces holding it. By late March, 1927, Shanghai (outside the International Settlement) was in KMT hands.

Having the Unions and Communists hold the city freed NRA troops to fight elsewhere, but when Chiang arrived in the city, he was not happy. Once in control, the Communists led daily demonstrations denouncing imperialism and demanding that the International Settlement be returned to China. Sporadic labor strikes broke out, often targeting foreign-owned businesses. The KMT had been stung by the anti-foreignism when the Expedition had captured Nanjing — the so-called Nanking Incident — and was eager to assure would-be foreign allies that the KMT was a reliable Chinese partner.

So with the Northern Expedition paused at China’s longest river (there were no permanent spans over the Yangtze until the 1950s), Chiang and his allies resolved to rid themselves of these meddlesome communists. On April 6 — the day after KMT left leader Wang Jingwei left the city — Chiang met in Shanghai with the head of the Green Gang, an organized crime syndicate, to coordinate the purge of the Communists. The city’s foreign community gave its approval to the plan as well.

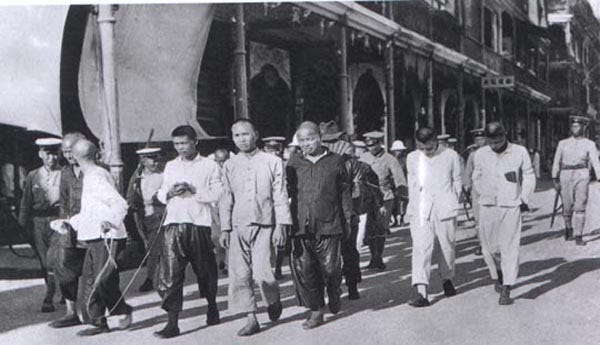

On April 12 — after a week of pressing the Unions to disarm and moderate their rhetoric, and transferring army units sympathetic to the Communists — Chiang enacted his plan. Before dawn, the Green Gang’s proxy paramilitary launched a series of attacks against union headquarters, and NRA soldiers were enlisted to carry the fight against the Communists, even though they were formally allies. Communists were rounded up and executed; hundreds, perhaps thousands, were killed. The following day, when workers and party members gathered to protest, troops opened fire on protesters, killing more than one hundred. All across Shanghai, soldiers and thugs rooted out Communists and their supporters, shooting first and asking questions later. Soon, a “White Terror” was launched across China; its expressed aim was to purge the party of Communists, though it went much further. Historian Rebecca Karl writes that more than a million people were killed, most of them peasants.

The purge was grimly effective. Karl writes that of 60,000 Communist Party members, only 10,000 survived 1927, and all of those fled or went into hiding, many in remote rural areas.

Chiang achieved his immediate goal: his leadership was assured, the Northern Expedition could go forward, achieving its goal of unifying China under KMT rule. The “Nanjing Decade” began when Chiang established his capital there in the wake of the purge.

But the greater legacy of the Shanghai Massacre was its impact on the Communist Party, which would, against all expectations, reshape the history of not only China, but the world. Mao Zedong, who had been writing his “Report on the Peasant Movement in Hunan” at the time of the purge, was a mid-level cadre. His vision of a peasant revolution in China was at odds with the party leadership, and also with the Soviet advisers who guided CCP policy. Moreover, dozens, perhaps hundreds, of officials stood between Mao and the party leadership. But after 1927, the Marxist orthodoxy of the party was shattered: there was no longer a Communist presence among China’s urban proletariat. And the people who advocated the conventional approach to revolution were mostly dead or in exile; those who (like Mao) endorsed a peasant-led revolution could offer a suddenly more appealing option. Catapulted to the front of the queue by Chiang’s purge, Mao became a party leader.

It would be a few more years until, at the Zunyi Conference, Mao became the unquestioned leader of China’s Communist movement, but would it have happened at all without the 1927 Shanghai Massacre? Probably not, or at least not so soon.

Chiang Kai-shek may have seen himself as fulfilling his destiny to unite the divided empire, and he may have done so, but not in the way he intended. It would be another two decades of war and revolution before China recovered (for the most part) its Qing boundaries, but it would be Mao — enabled by the purge that eliminated his rivals for power — and not Chiang, who would preside over it.

Share this post